High-conflict countries (and people) have enemies. That is one of their signature traits. Blame, remember, is the ultimate renewable resource. And one targeted group is never enough. It’s a vicious cycle, one that can only be stopped when enough people exit the game.

In the summer of 2020, police officers became the enemy, as you might remember. One retired officer, whom I’ll call Tom to protect his privacy, had spent 23 years on the job and always felt proud of his career. By then, he was living in Texas and working in schools. He’d had nothing to do with the murder of George Floyd, Jr., in Minneapolis. But in high conflict, there are no shades of gray; all cops were bastards, remember.

“I became, let’s just say, dangerously depressed,” he told me. “Suddenly, I was the villain, and my profession was evil.” His daughters stopped telling anyone about his career, out of fear of judgement and retribution. He watched a police station burn on TV. It was deeply disorienting. He went through the house, gathering up all his awards and anything that identified him as a police officer, and put everything in a box, deep in his closet.

At first, he felt profoundly sad. “I wasn’t necessarily thinking about suicide, but I was definitely wondering if my life had been spent in vain.” Then, watching the images of rioting and vandalism on the news, sadness was replaced by fear. He imagined what might happen to America without police officers. “I feared the looting of my home. I feared gangs of armed individuals casually committing robberies. I feared an upside-down existence because people could do whatever they wanted with impunity.”

This is what high conflict feels like, in a family or a country: grief, anger, and, pulsing underneath everything, a deep current of fear.

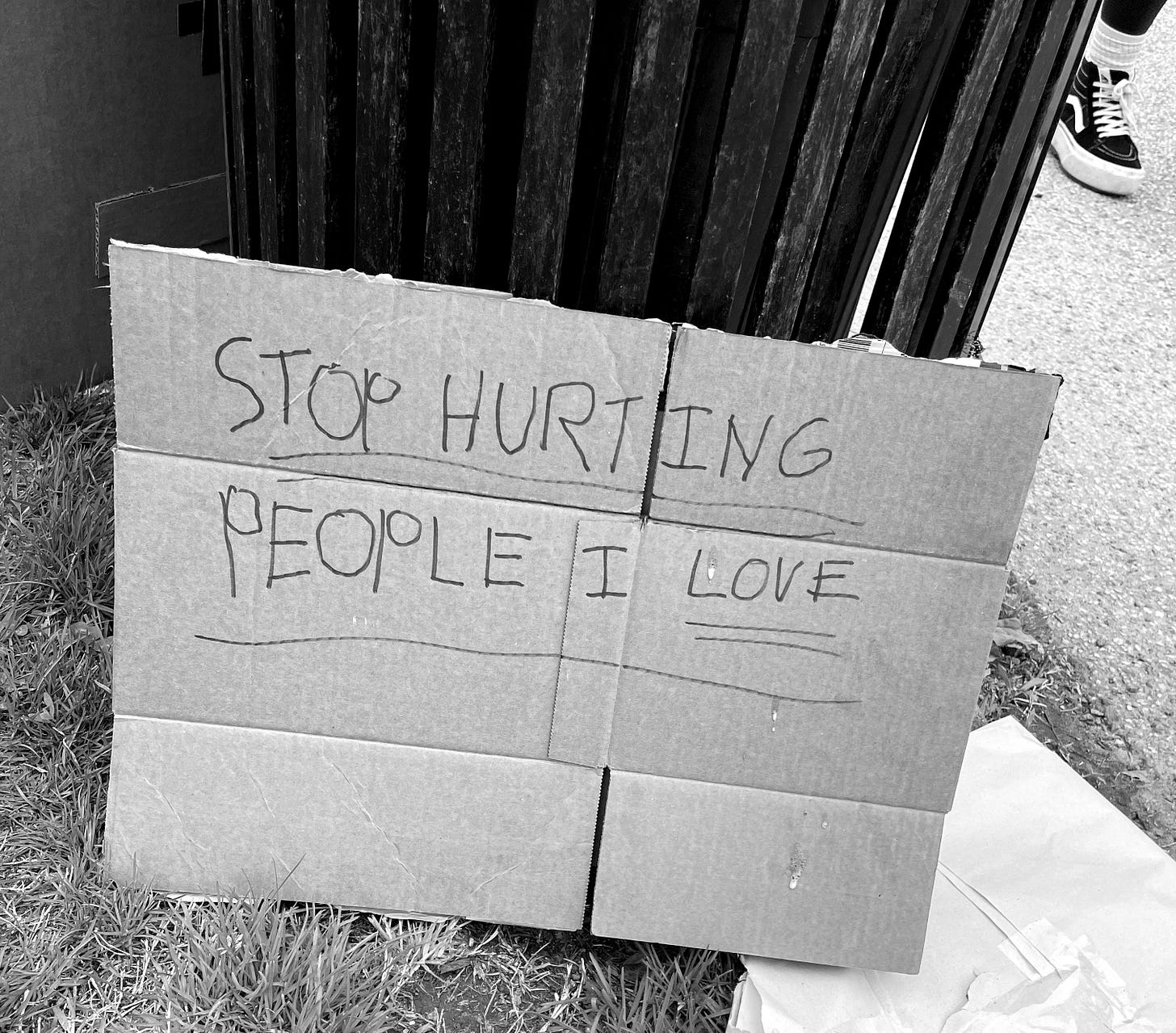

Where do those feelings go, after they flood tens of thousands of Americans on one side or another? In many people, they find the next nearest target. Maybe their neighbors, their school board or a politician they’ve never met. Or maybe they harm themselves, tragically. In this search for a convenient enemy, we get ready assistance from conflict entrepreneurs, who stoke the embers of fear and revenge.

Hurt people hurt people, as the old saying goes. In interviews with more than 200 people involved in conflicts in Somalia and Rwanda, the psychologist and physician Evelin Lindner found that humiliation permeated their stories of victimization—and persecution. Often these stories were told by the same people. Feelings of humiliation drive acts of humiliation, and on and on the cycle goes. Humiliation can become an obsession, she found, “as significant and consuming as any form of addiction or dependence.”

Join myself and Good Conflict co-founder Hélène Biandudi Hofer for a free, public webinar on how to live with fear and uncertainty (of all kinds) on June 12 from 12:30-1:30 pm ET (9:30-10:30 am PT). We’ll be joined by our special guest, Prof. Kate Sweeny, who studies uncertainty and worry.

Refusing to be Played

But some people, in every high conflict I’ve ever seen, find a way to resist this temptation—or escape its spell, once captured. They step out of the dance of polarization, breaking this cycle.

These are the stories I am most interested in telling these days. Not stories about resisting Trump or any particular politician; stories about resisting high conflict. In ourselves and in our communities. Because there will always be new conflict entrepreneurs, ready to exploit our fear. The better question is, how do we become harder to manipulate? And what would it take to inoculate an entire society?

In the last newsletter, I wrote about a friend of mine who works for the federal government and found herself being suddenly villainized and targeted, without regard for her work or her worth. Overnight, it seemed, her assumptions about the world and her place in it had been turned upside down.

Seeing this, Tom reached out. He couldn’t help but see the pattern here. In 2020, it was police officers (and others). In 2025, it’s federal workers (and others).

“Somewhere, someone is having just as dark a day as I was,” Tom wrote to me. “We are experiencing a pendulum, where it swings from ‘Right’ to ‘Left.’ If one side pulls it hard enough, it will swing back the other way, just as far as it was pulled.” In the past, this might have created some kind of equilibrium; but today, it doesn’t seem to work that way, as Tom explains:

“I’ve long hoped that, like a pendulum, it would decelerate to a happy middle. But as I age, I wonder if the pendulum is actually inverted. An inverted pendulum will never settle back in the middle; it will [just] stop on one side or the other. This is sad to me.”

We all have whiplash by now. One day there’s a rush to embrace DEI, and then there’s a stampede to erase it from existence. It’s dizzying and destructive, and it will probably continue. Because it’s not about the letters or even the ideas. It’s also about the humiliation underneath.

It is sad to watch as we perpetuate our own suffering, identifying new enemies all the time. The list now includes journalists, police officers, judges, the FBI, all Democrats, all Republicans, Disney, Target, federal workers, trans people, teachers, academics, Tesla owners, black people, white people, Jews, Palestinians, immigrants and…well, you get the idea. Who will be next?

Tom, like many of us, is tired of being jerked around. It is no way to live. His advice for everyone else being demonized right now: “Stop pulling the pendulum. Don’t answer violence with violence, or fear with fear.”

How to Resist High Conflict

What can we do instead of responding in kind? Here is a short list of ideas that I hope we can keep adding to together in the months to come:

1. Talk about the Understory: Sen. Lisa Murkowski did this recently when, instead of reverting to the usual talk track on tariffs and Trump, she bravely spoke about fear instead. (For more, see our post about this on Good Conflict’s Instagram channel here.)

2. Decline to Take the Bait: Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese did this beautifully when he rejected the false binary of either surrendering to Trump’s tariffs or matching them. (As we describe in another post here.)

3. Surprise Your Enemy: Here is a podcast episode I recently got to make with my friends at Slate’s How To! show—about a school superintendent and her school-board nemesis. How did they step out of the dance of high conflict? It’s an unexpected story that features roaches, flowers and third chances.

4. Limit Your News Consumption: Tom, the retired police officer, identifies this as the most valuable step he took. These days, he tries to stay up-to-date on his family, his community and his small circle of friends. “While the majority would say that I am now less informed, I will argue that personal peace is always more valuable than knowing everything.” Amen to that. (For more on how journalism needs to evolve, based on what we know about human psychology, check out this hopeful and wise new On Being podcast interview with my friend and fellow journalist David Bornstein.)

5. Build: Look, we cannot be a civilization without institutions that we trust. This is the foundational problem, underneath everything else that’s going on right now. So what then? Look around. Where might you be able to help build something that most Americans (or at least most of your neighbors) will trust?

It might mean helping news outlets change what they do and how they do it, as Joy Mayer and her team at Trusting News have been doing for almost a decade; or it might mean creating a Unity Council in your town, like the residents of Hingham, MA. Maybe you could help faith leaders build resilience in your town, with help from the Multi-Faith Neighbors Network. Or join the Builders Movement for inspiration and ideas (and some of the most engaging, depolarizing content on social media today).

None of this is possible if we allow ourselves to feel humiliated—and then go on to humiliate others in return. Breaking this cycle is extremely difficult. That’s why we have to help each other visualize what it looks like.

What else have you done—or seen others do—to resist high conflict lately? Email me at amanda@amandaripley.com and let me know. Together with my colleagues at Good Conflict, we’re collecting and sharing stories and tactics for anyone who wants to do conflict differently. And one thing we know for sure is that we cannot do it alone.

Here’s to exiting the blame game,

Amanda

3 Good Things

If you haven’t read An Immense World by Ed Yong yet, stop everything and go get it. I’ve been reading 10-15 minutes each morning to remind myself how dazzling the world actually is, and how much of it I have yet to understand. (Did you know we only see 1% of the colors that birds can see?? Meanwhile, for dogs, the sky is blue but grass is…white! And don’t even get me started on what elephants can smell…)

Did the presence of the legendary soccer player Mohamed Salah actually lower hate crimes in Liverpool? Read about it in the Better Conflict Bulletin.

This July, we’ll be hosting a special Good Conflict Master Class exclusively for educators. Why? Because no one (no one!) deals with more dysfunctional conflict, in our experience, than educators. And we want to help. So please share our Summer School announcement with any college administrators, school superintendents, principals, teachers, school board members or parents you know who might be interested in having better fights next school year.

© 2025 Amanda Ripley. See privacy, terms and information collection notice.

Top Image: Wheel of fortune by Arthur Rothstein, 1940. Via the Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2017779956/

Always a treat to read your writing! This is such timely wisdom.