The Protest Trap

We all need to do something useful with fear, rage and grief. The question is, what? Three lessons from the research.

Just after 11 o’clock in the morning on Oct. 14, 2022, at the National Gallery in London, two protesters from the climate activist group Just Stop Oil slipped under the velvet ropes protecting Vincent van Gogh’s Sunflowers painting and threw two cans of orange Heinz tomato soup on the artwork, which was protected by glass.

It was one of three dozen protests at art museums worldwide that year. The goal was to attract media attention, and it worked, in a way, sparking over a thousand stories all over the globe, from South Africa to China to Australia.

“We are not trying to make friends. We are trying to make change,” a spokesperson told The Guardian afterward. “And unfortunately, this is the way that change happens.”

But wait, is this the way change happens? It’s a logical theory: Drive attention to a serious problem in hopes that it will galvanize public support, which will put pressure on decision makers to make positive change.

But does it work? Or more to the point, when does it work?

Magical Thinking

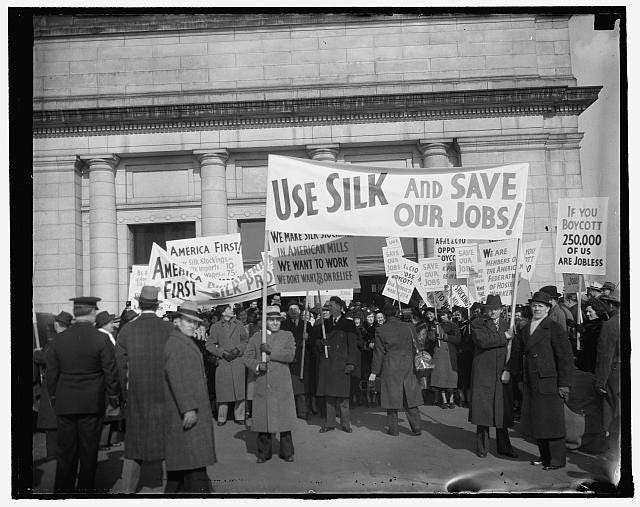

We’re living in an age when many things need to change—and more people are depending on protests of all kinds to make that change happen. As the war in Gaza rages on, this theory of change is being tested on college campuses and in parliaments and board rooms around the world. The demands to pick a side, to speak up, to insist—they all depend on this hypothesis being true.

To be sure, high-profile protests can accomplish a couple of things right away, even without creating change: they can make suffering people feel less alone, which is important. And they can make the protesters themselves feel better--like they are doing something. And this matters, too. At a time when we’re inundated with constant reminders of what is going wrong, and offered almost no suggestions about what to do about it, we are all desperate to reclaim a sense of agency. We can’t just sit here doing nothing.

That is a beautiful impulse, one we should encourage. The best way to encourage it, though, is to make sure we’re doing something. What really leads to change? What ends wars? Even better, what prevents wars? And where is my own sphere of influence?

If we don’t start with those questions, we can fall into the protest trap: We get so seduced by the magnetism of the demonstration itself that we start to really believe that the protest is the change. It’s a form of magical thinking, the kind that is very hard to resist in an age of high conflict.

All of this activity can serve as “work avoidance,” as a conflict expert I admire recently put it. We are so busy demanding that people make a statement or pledge their allegiance that we can fail to do the harder work that really, truly makes a difference.

What does prevent war?

If I had to distill the research into one word I’d have to say (get ready to be disappointed…): Relationships. That is the brutal truth. Relationships make it harder for humans to humiliate, dismiss and degrade each other. Relationships are how we hold each other accountable. They’re how we pass laws and enforce them.

Relationships are not enough, on their own, but it’s hard to find humans living in peace and dignity without them.

“I have had the privilege for nearly half a century of making films about the U.S….with all of its majesty, complexity, contradiction and controversy,” the filmmaker Ken Burns said at Brandeis University’s graduation this summer. “If I have learned anything, it’s that there is only us. There is no them. And whenever someone suggests to you…that there’s a them, run away. It’s the surest way to your own self-imprisonment.”

So what then? How do we build relationships at scale, quickly, to change the world? Well, this is what successful social movements do, right? They create a web of rapidly replicating relationships that expands geometrically.

OK fine, but what makes some movements successful–and not others? In 2022, the nonprofit Social Change Lab identified three factors that predict success:

1. Nonviolence. Like others, they found that nonviolent movements are significantly more likely to lead to change. In their book Why Civil Resistance Works, Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan concluded that nonviolent movements were more than twice as likely to succeed as violent ones. That’s largely because of No. 2.

2. Large Numbers. Size really matters. The more people you attract to your cause, the more likely change will happen. Nonviolent, flexible movements can attract and retain larger, more diverse followings. (Because violence, by contrast, is scary, and many mentally stable people tend to disengage when they see it.)

3. Timing. Most of the levers of change are outside the control of the protesters. Public opinion, media attention and luck can create openings, all of a sudden. So it’s important to organize in advance, so you can seize those openings when they happen.

To sum up: attention does not lead to change all by itself. And it can backfire. In 2022, researchers from the University of Pennsylvania did two surveys of over a thousand Americans to see what they thought about attention-grabbing protests—like the tomato soup incident at the National Gallery. Nearly half of those surveyed said that these kinds of protests actually decreased their support for the cause. Only 13 percent said they boosted their support, according to the findings by climate scientist Michael Mann and his colleague Shawn Patterson Jr.

“Whenever someone suggests there’s a ‘them,’ run away. It’s the surest way to your own self-imprisonment.” — filmmaker Ken Burns

So go ahead. Issue a statement. Set up an encampment. Throw some soup! But don’t think you’re done. And if your protest is shredding more relationships than it’s creating, maybe it’s time to pivot.

If you want to stop violence and injustice and create lasting peace, push your campus, company or country to use their power to cultivate honest, unlikely relationships in conflict. Like this and this and this. It’s how change happens.

Here’s to making magical soup, together,

Amanda

My New Book!

It’s been sixteen years since The Unthinkable came out, but it feels more like sixty. A lot has happened: A global pandemic. Smartphones and social media. Distrust and polarization. Arctic zombie viruses! Cryptoworms! Oh my!

For all these reasons, I’m proud to announce the new and improved Unthinkable, out August 20th, with extensive new material on the pandemic, climate change, social media, how to rebuild trust and other, more recent calamities, from plane crashes to earthquakes.

The bottom line: Disasters are more frequent and more costly than they were when this book first came out. But they’re also more survivable.

It helps if you know what to expect. Your brain, your body and your neighbors will not behave the way you think. Reality is better in some ways (and weirder in others). I hope reading this book will leave you more confident about what matters, how to prepare and whom to trust. Let me know what you think!

Have the Right Fight

Two years ago, I started Good Conflict, a media and training company, with my friend and fellow journalist Hélène Biandudi Hofer. Together, we’ve now trained over 2,000 people and learned incredible, surprising lessons about how to communicate in an age of runaway conflict.

This fall, we’ll be sharing our best tools, tips and tactics in a highly interactive Good Conflict digital masterclass. Sign up to get updated when the course is live!

Meanwhile, for tips and tricks on staying sane in a high-conflict world, follow us on LinkedIn, Instagram and Facebook. And please share your own stories and lessons learned. We love hearing from you!

P.S. Want to make government more trustworthy?

A group of polarization researchers wants your suggestions right now. Submit ideas for reforms here. The best ones will be studied, tested and shared widely.

© 2024 Amanda Ripley. See privacy, terms and information collection notice.

Thank you, Amanda, for your thoughtful, important and ongoing work! One comment: Ken Burns' commencement address was great, and at the same time, the one quote you use is indicative of how hard it is for us to not think in terms of us vs. them. If there is no "them," who is the someone we're running away from? Rather than run away, a better choice might be to engage. Build relationship on the odds it may gain you influence, and maybe teach you something about the human condition we all share.

Woot! I'm excited for the new (old...) book. Hope all is well for you in this hot summer.