What You're Missing

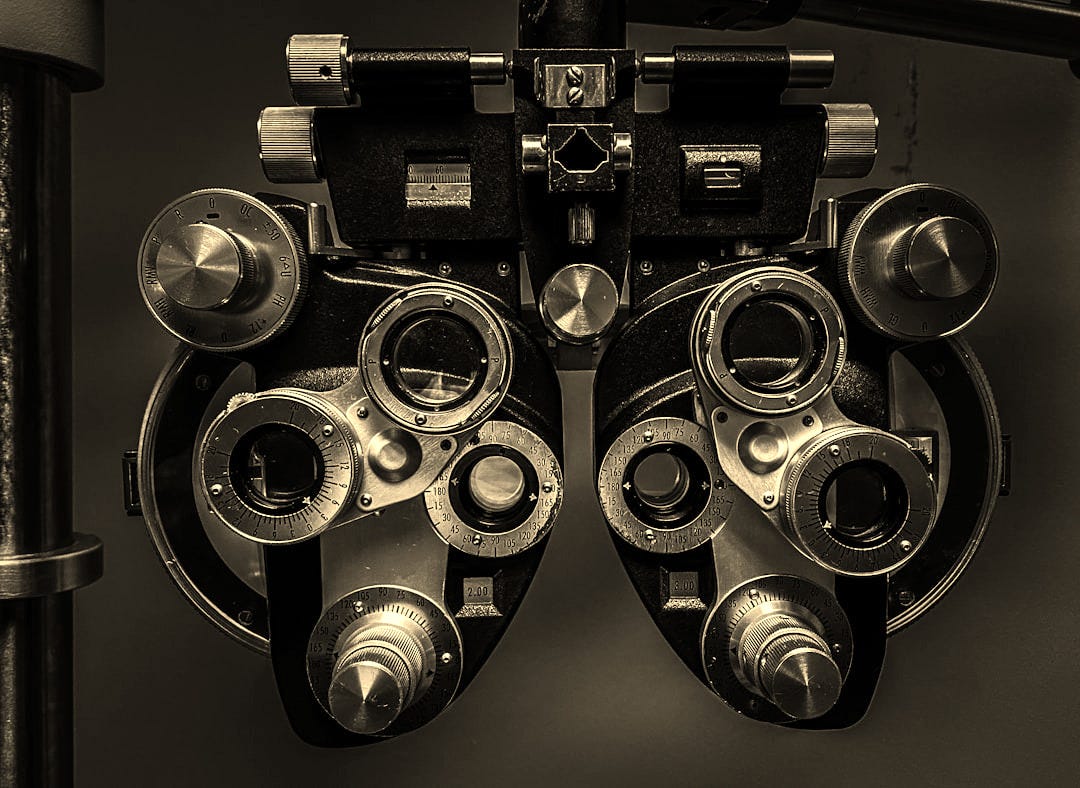

Glasses help you see the world more clearly. What if the news did, too?

“You can’t depend on your eyes when your imagination is out of focus.” — Mark Twain

Next year, when the FBI releases data for 2025, it’s likely to announce the lowest murder rate ever recorded (since such estimates began back in 1960).

Let me repeat: The United States of America is on track to have the lowest recorded murder rate since The Flintstones premiered on TV.

This extraordinary milestone, explained with care and caution by the data analyst Jeff Asher in his excellent newsletter Jeff-alytics, reflects a continuation of the decline in homicides that began in 2023 (after a big pandemic-era spike). And yes, we should debate why this decline is happening and how to make sure it continues.

But also, sweet mother of God. Can we just take a minute here? This is big. Like, ticker-tape-parade-and-free-hot-dogs-and-dancing-in-the-streets BIG.

At the very least, most Americans should know about this milestone, right?

Unforced Errors

The most basic job of the news media has always been to inform the public. And yet, in a July YouGov poll, Americans were asked if murder rates in U.S. cities have increased since 1990. (In fact, murder rates in those dark days were almost twice what they are now.) But just over half of those surveyed said Yes, murder rates are higher now.

That is a stunning error about a very basic reality. This misperception is particularly rampant among Republicans and older Americans. And you might say, well, that’s because certain news outlets favored by those groups (including Fox News and national network news, according to this study) tend to leave people feeling more frightened than they need to be. These outlets overemphasize scary, highly salient crime stories without regard to their frequency.

But almost half of Democrats made the same mistake, believing the literal opposite of what is true about homicide rates. That’s partly because exaggerations about lawlessness and danger extend well beyond TV news to social media and politics. Conflict entrepreneurs* are richly rewarded these days for convincing Americans that we’re our own worst enemies.

Now, you might say there’s nothing we can do to stop this sensationalism. Humans are wired to click on fear-mongering headlines. We have a negativity bias! And that is also true.

And yet, in some industries, when there is a known and predictable error in human perception, the most innovative entrepreneurs try to correct for it. They invent glasses so people can see better, rear-view cameras so people can drive better and spellcheck so people can write better. And a lot of their customers seem to appreciate this.

Shouldn’t there be a way to help us improve our vision, if we so desire? Couldn’t a media outlet offer to help reduce our biases, rather than making them worse?

For example, what if, in the aftermath of the horrific murder of Charlie Kirk earlier this month, more journalists had tried to help the public understand political violence and how to prevent it—rather than adding to the fear and speculation (or falling into the trap of trying to label the murder victim as good or evil, before the funeral was even held)?

News for Humans

Here’s an example of what news designed for humans could look like. Two days after Kirk’s murder, Sean Westwood, director of the Polarization Research Lab, wrote a short and clarifying Politico piece. After chastising political leaders for using apocalyptic language and ramping up the threat level, which makes violence more likely, here is what he said about your fellow Americans. Notice how he works to correct perception errors, rather than exacerbate them:

To be clear, a mass movement of political violence is not happening. For the past three years, I have tracked public support for political violence, and the data are unequivocal: fewer than 2 percent of Americans believe political murder is acceptable. The core problem is not a widespread desire for violence, but a profound misperception of the other side.

My data also show that Americans estimate nearly a third of their political opponents support partisan murder. This belief that one is facing a vast, murderous faction — rather than a few isolated extremists — creates a phantom enemy that makes the country feel far more dangerous than it actually is.

This climate of fear provides the context for the rise in the murder of public officials, attacks on Jews, threats toward election workers and attacks on government facilities. While this trend is serious and dangerous, it is one of individual radicalization, not a coherent mass movement. It is a whisper aimed at the unstable man in his basement — validating his terror of a murderous opposition and giving his private rage a public warrant.

Westwood is not a journalist; he’s a researcher filling a vacuum left by the media (and a fine writer, to boot). Every week, his lab asks a thousand Americans how they feel about political violence and continually tracks other key metrics of polarization (such as the level of contempt and disdain in elite politicians’ speech). The Lab’s easy-to-use and constantly updating dashboard offers all of us a much sense of the threat and the climate than any news outlet I am aware of.

Around the very same time, Jonathan Stray, a scientist at the Center for Humane-Compatible AI, wondered if the vicious social media posts he was seeing were actually typical. So he quickly analyzed a small, chronological sample of Twitter and Bluesky posts about Kirk’s death—and found that only about 1.5% called for more violence. Which was good to know. But why is he doing this all on his own?

These platforms could help us understand proportionality and reduce polarization on their own, as Stray explained in his fascinating newsletter, the Better Conflict Bulletin:

As a media algorithm designer, the question I’ve been asking myself for the last two days is, what should social media have done here? Clearly, the answer isn’t hiding the event — it’s legitimately major political news. But there’s a happy medium somewhere, and the most vitriolic responses are neither representative nor helpful. Fortunately, we do know how to build social media algorithms that reduce conflict rather than stoking it. It remains to implement these techniques.

In the meantime, why couldn’t news outlets help us calibrate what we’re seeing on these platforms? After all, the questions Stray and Westwood are trying to answer are fundamental:

How often is this terrible thing happening?

How is the terribleness changing over time?

What can be done to reduce terribleness in the future?

So why do those questions go unanswered in most news stories today?

The Top Distortions that Can Lead to Depression

In his book, Feeling Great, Dr. David D. Burns lists common cognitive distortions that can lead to depression and anxiety. These are what Burns and his colleagues call “thinking errors,” and they happen to all of us.

When I looked at this list for the first time, I felt my heart sink. I saw a checklist of journalism conventions—things my colleagues and I did without thinking twice. Including:

Overgeneralization

Discounting the Positive

Jumping to Conclusions

Fortune Telling

Labeling

Blaming

Let’s take one example: Discounting the Positive. In our lives, this is what happens when we focus disproportionately on criticisms, problems or failures—and disregard good things that happen. We all have friends like this, and they are hard to be around. In journalism, this is, simply put, “the news.”

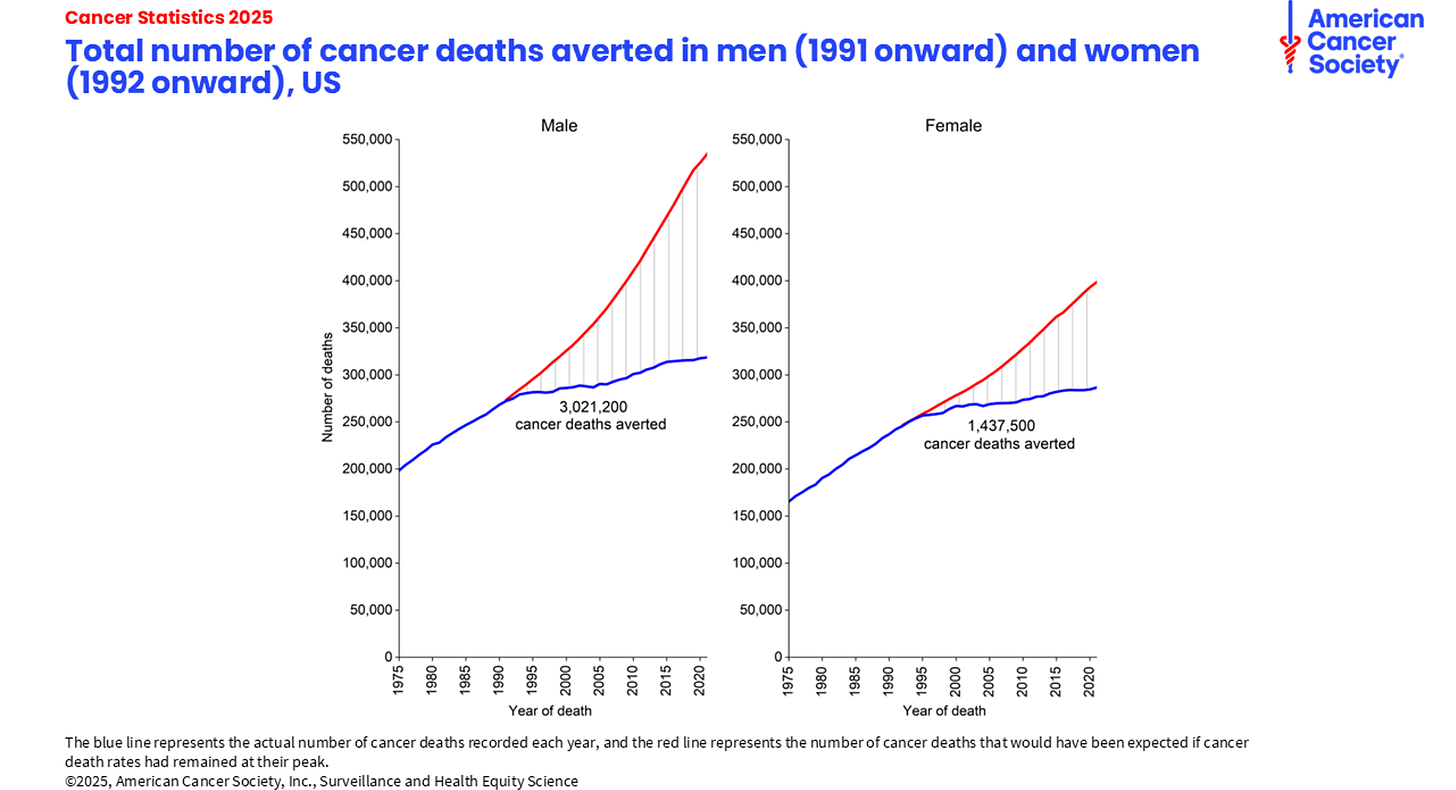

For example, earlier this year, a new report by the American Cancer Society showed that the cancer mortality rate in the United States has declined by 34% from 1991 to 2022, preventing approximately 4.5 million deaths.

Interestingly, citing the exact same report, the New York Times ran this story: “Cancer’s New Face: Younger and Female.”

Instead of focusing on the 4.5 million not-dead people, in other words, this story looked at the same report and emphasized the fact that certain cancers are getting detected more frequently in younger women than in the past.

Both trends are true and important. One is hopeful and energizing, and the other is frightening and paralyzing. This is what it means to “discount the positive.”

If the New York Times were a person, it would need therapy.

Right now, four in ten Americans are avoiding the news because it is so depressing. Couldn’t more hopeful (and accurate) coverage be a way to lure those people back?

I suspect that the reasons for distorted thinking in journalism run deeper than the business model or the primal impulses of audiences. After all, people are also more likely to click on porn, but that is not something The New York Times generally delivers. No, I think there is something in the culture of the profession that views hopeful news as soft and unserious—and depressing news as important and powerful.

I think this because I used to feel this way, too. Somehow, it felt stronger and safer to focus more on what’s broken than on what’s working. Cynical people are often perceived as smarter, and many journalists (especially at places like the New York Times) want very badly to look smart. All the prestige and prizes go to the journalists who expose corruption and evil, whose stories make it seem like no institution can be trusted. They are the heroes, and I wanted to be a hero, too.

It’s also true that I no longer feel this way. Maybe there is hope in that. These days, some of my favorite stories are about stories of people trying to solve problems against all odds (like, for example, this one or this one).

And I’m not alone. There are, today, more journalists than ever trying to do journalism for humans. The Solutions Journalism Network has trained over 76,000 journalists to rigorously cover efforts to solve problems—not just problems. A Poynter program has helped over 500 journalists try to shift their crime coverage to focus more on public safety and crime trends as opposed to sensational, breaking-news stories. Right here at Good Conflict, Hélène and I have helped thousands of journalists and non-journalists alike to investigate more accurate (and more interesting) stories about the world, our biggest controversies and each other.

I’m convinced there is huge, unmet demand for a different way to make sense of our chaotic world, and more creative people than ever are trying to meet that need. Some efforts are serious and data-driven, and some are endearing and hilarious—like this one, from Instagram.

What about you? How do you make sense of what is happening and put our problems in perspective? I hope you’ll let me know in the comments below.

Here’s to sense-making, ticker-tape parades and spelling bees,

Amanda

“Action absorbs anxiety.”

One last thing. If you are worried about the rise in political violence in America, I am with you. It’s terrifying to watch this horror show play out on our phones and TV screens. But as the former journalist and current podcaster Dan Harris reminds us, the best thing to do in a time of fear is to take action. Do something. So here are a few things to do:

Join the Builders Movement and follow their fantastic Instagram channel to find ways to resist contempt and the us-versus-them thinking that leads to high conflict and violence.

Call your elected officials and ask them to do more than condemn violence; invite them to negotiate a nonaggression pact with their colleagues across the aisle. More on what this looks like and why it matters here.

Find your town on the National Civic League’s Ecosystem Map to see which organizations you could join or support to help build a healthier democracy. There are over 11,000 organizations on here, so there’s probably one that needs your help.

*P.S. My Good Conflict co-founder Hélène Biandudi Hofer and I just did a free webinar on how to deal with conflict entrepreneurs, in case you’re interested. You can watch the recording here.

© 2025 Amanda Ripley. See privacy, terms and information collection notice.

I try to put things in perspective by trying to "reframe" them- creatively come up with a completely different reason why someone is doing something that the one that immediately comes to mind. For example, is the person yelling at a store clerk severely sleep deprived? Or do they have an ill family member? Even if I'm wrong, I end up treating them with compassion and then that's reflected back to me.

Thank you for ALL of this, Amanda. I started researching how Builder and Solutions Journalism can be part of my work and part of my hope.